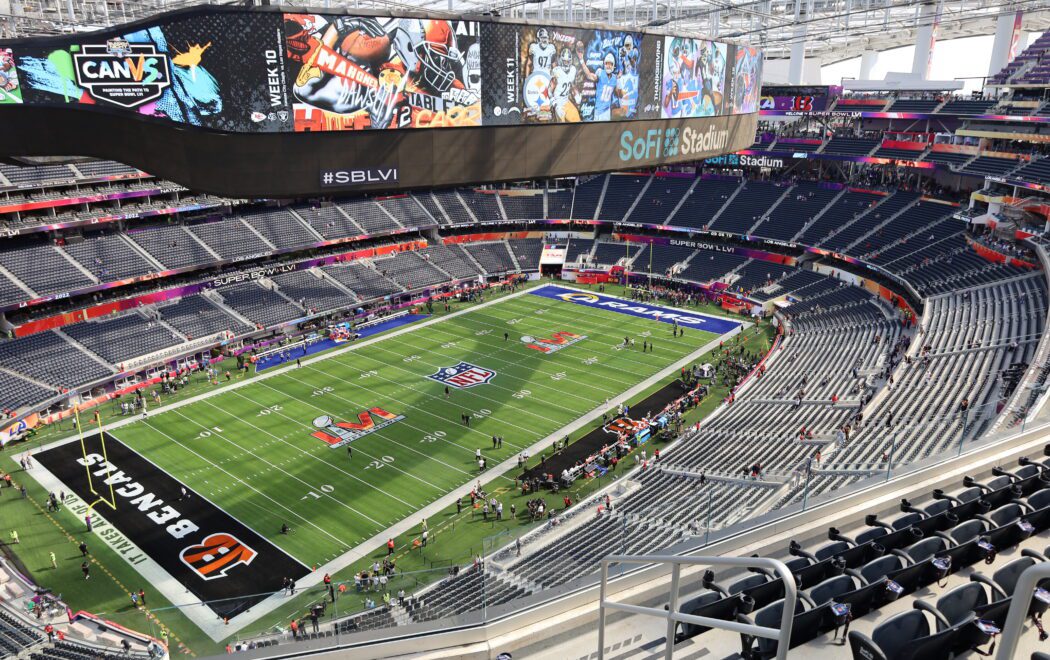

As a former NFL Director of Gameday Technology and Stadium Infrastructure who helped plan and organize 22 Super Bowls, I feel it every year as the big game approaches. There is a familiar pressure that settles in my bones, driven by the knowledge that every aspect of televising the game has to work. The network diagrams, the capacity models, Wi-Fi, and backup systems all have to be flawless. For fans, the Super Bowl is a spectacle, something to lean back and enjoy. For those responsible for a stadium’s technology, it is the final mile of a marathon that began years earlier.

This year, as Levi’s Stadium prepares to host the game, I cannot help but think about what comes after Super Bowl. Sixteen stadiums across the United States, Canada, and Mexico are already deep into their own countdowns toward the 2026 FIFA World Cup. The venues are different, and the scale will be even larger, but the underlying challenge is the same: how to make complex, high-stakes technology perform flawlessly when the entire world is watching.

I spent more than two decades inside NFL venues as they counted down to Super Bowls in places like Atlanta, Jacksonville, New Orleans, and New Jersey. I have seen how much invisible work it takes to make a few hours of game time look effortless. Now as a consultant for World Cup preparations, the process underway across North America has reminded me how little of that story ever gets told, even though it shapes what stadiums become long after the final whistle.

These global events are not just bigger games. Some are bid-driven productions where cities compete for the right to host, and all venues commit to meeting demanding technical, security, and broadcast standards that push their infrastructure far beyond everyday operations. When they work, the results look seamless. When they are planned thoughtfully, they can leave something even more important behind: stronger, more capable stadiums.

Two years out: future host city commits to the specs

Long before anyone worries about Wi-Fi speeds or camera angles, contracts to host large-scale sporting events are won in conference rooms. For some events like the World Cup, cities and venues bid aggressively for the right to host. In doing so, they agree to a thick stack of technical, operational, and security requirements set by the event owners.

Those requirements exist for a reason. When hundreds of millions, or even billions, of people are watching, there is no tolerance for outages or improvisation. But those commitments also set the tone for everything that follows. Once you win the right to host the event, you are no longer just running a stadium. You are preparing to become a temporary global broadcast hub.

The smartest owners start thinking early about what will be temporary and what should be permanent. The overlay required to host a world-stage event often reveals where a venue’s core infrastructure is thin, and those moments create rare opportunities to invest in systems that will matter long after the event has moved on.

Months out: Designing a temporary city

A large-scale event like the Super Bowl or a World Cup match requires creating a whole out the sum of many fast-moving parts: its impact stretches across hotels, practice fields, convention centers, broadcast compounds, and sponsor pavilions.

All of those locations need connectivity, security, and redundancy. Broadcasters, carriers, sponsors, law enforcement, and league partners all arrive with their own systems and priorities. None of it fits neatly into a stadium’s normal operating model.

This is where experience matters. The challenge is not just adding capacity. It is deciding where temporary systems should sit, how they connect to permanent ones, and how to keep the whole operation stable while dozens of outside organizations plug in at once.

Weeks out: Building at speed

About a month before game day, the transformation becomes visible. Every system throughout the stadium is impacted: miles of cable, hundreds of temporary endpoints, temporary network cores, and additional fiber trunks. Broadcast switchers and carrier-grade radios will live in the building for a few weeks and then disappear overnight.

At this stage, the venue is no longer just a venue. It is a construction site, a data center, and a broadcast studio all at once.

Game week: Zero margin for error

When fans arrive, technology use increases. People who might check their phones a few times during a normal game now try to upload videos, post photos, and stream content all at once. On Super Bowl Sunday, network usage can spike 10 or 15 times higher than during a typical game.

At Super Bowl 59 in New Orleans, cellular networks carried more than 67 terabytes of data. Wi-Fi handled another 17 terabytes. Usage between cellular and Wi-Fi is tuned carefully so that should everyone reach for their phone at the same moment, the system doesn’t crash.

To make that work, broadcasters, carriers, and venue teams are sharing spectrum, fiber, and backhaul that were never designed to be used by this many independent systems at once. Even a few minutes of downtime can have a negative ripple effect through global broadcasts, sponsor activations, and league relationships that took years to build.

This is when every detail matters. Technology such as wireless microphones, backup power, redundant radios, and even toilets. We test it all, because when the world is watching, there is no such thing as a small failure.

Hours after: Teardown and restoration

When the game ends, the clock starts again. In some locations, teardown begins before halftime. Temporary networks, broadcast gear, and thousands of screens are pulled, packed, and loaded onto trucks. A Super Bowl can generate more than 10 semi-tracker trailers full of IT and video equipment alone.

The goal of the teardown is simple: return the building to normal as fast as possible.

But not everything leaves.

What stays behind

Not all upgrades are temporary, and that is where the real value lies. Temporary overlays often expose where a venue’s permanent infrastructure is thin, and the best owners use that moment to invest in the systems that will matter for at least the next 20 years, not just the next event.

Carriers leave behind new antennas. Venues keep new fiber runs. Security and monitoring systems improve. When these events are approached strategically, they quietly deliver millions of dollars of lasting improvements.

With the World Cup coming, 16 venues now have that opportunity in front of them. If history is any guide, the venues that plan carefully will not just host a few great matches. They will emerge with stronger, more capable stadiums for decades to come.