In the basement of a gleaming MLS stadium that opened just three years ago, beneath the LED ribbons and IP-connected systems, there runs a cable plant engineered for workflows that are no longer the default. Forty-two thousand feet of triax, coaxial cable’s beefier cousin, run through conduit and cable trays, connecting camera positions to a broadcast compound. The cable itself cost $175,000. It is reportedly used only eight times a year.

This is not a mistake. It is a specification.

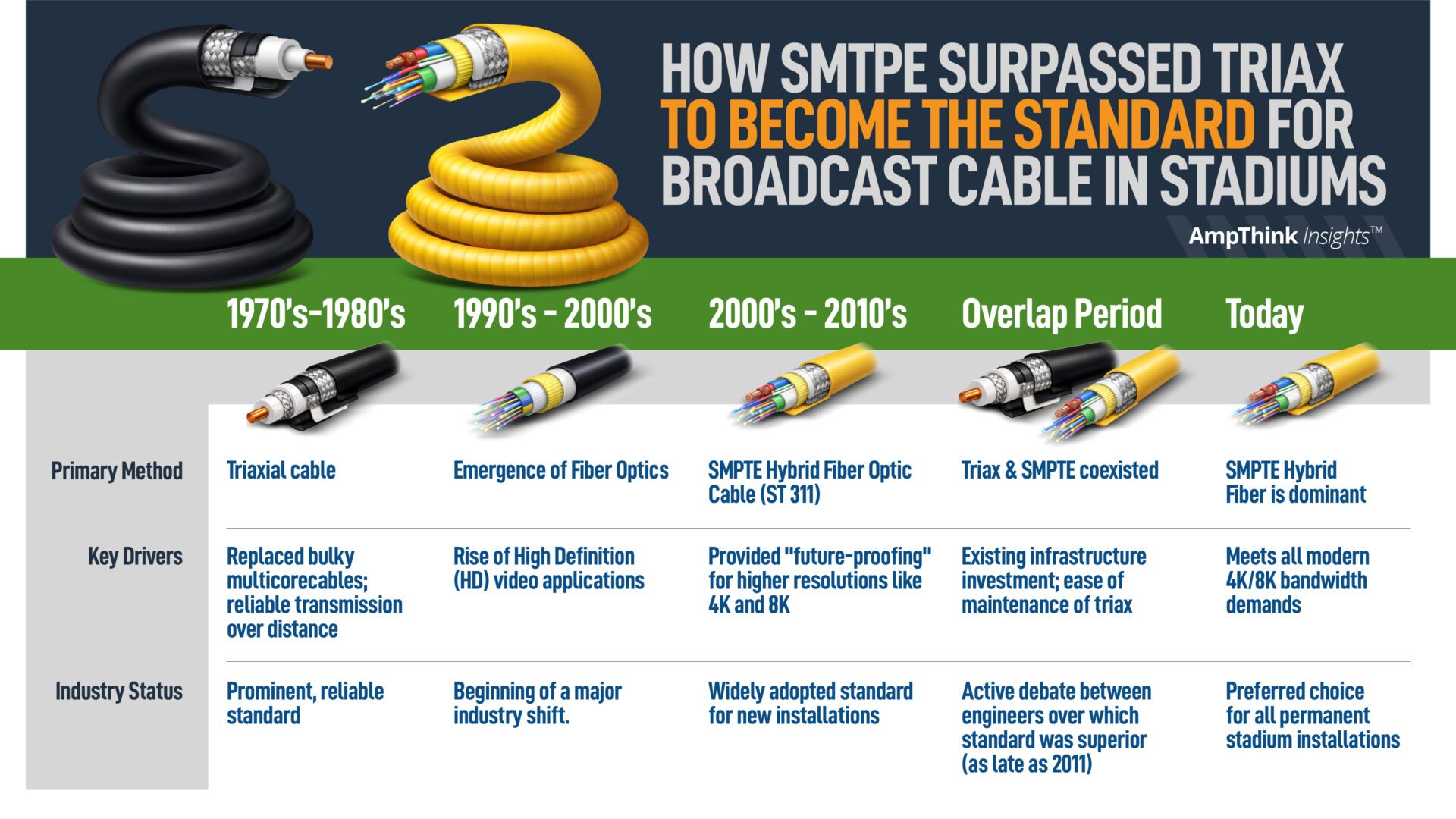

For decades, triax was the invisible backbone of sports broadcasting, the technology that made mobile camera work possible and reshaped how fans experienced live sports. A single triax line consolidated everything a broadcast camera needed: power, video, intercom, tally signals, control data. It was elegant infrastructure, dominant through the 1980s, 1990s, and into the early 2000s, when stadiums were built with the assumption that triax would last as long as the concrete.

Then bandwidth caught up with ambition. As production moved to 4K and HDR, triax hit practical limits in many implementations, often cited around the mid single-digit gigabits per second range, and typically aligned to 1080p-class workflows. SMPTE hybrid fiber became the prevailing direction, threading two to four single-mode fibers and copper conductors through a single jacket and offering bandwidth that triax could not approach. Modern broadcast trucks rewired themselves. Studios upgraded. The future moved on. And yet, walk into certain new stadium projects today, and the specifications still call for it.

Some league and broadcaster venue standards still reference triaxial cable as part of venue design requirements, even as the broadcast industry they serve has largely shifted. It is a peculiar kind of architectural irony, infrastructure designed for expectations that no longer match day-to-day reality.

Triax is not the subject here. It is the lens. What it reveals is a broader set of questions that every stadium eventually confronts, usually too late: When do you retire a technology that no longer plays a central role in operations? Why do certain systems persist long after their original purpose fades? And what makes the decision to cut the cord so difficult, even when the financial case appears straightforward?

Understanding why triax remains in place, and what it costs to keep it there, offers a window into the larger challenge stadiums face as they balance legacy expectations, partner requirements, capital planning, and the relentless churn of their technology stacks.

The Price of Preservation

If money were the only consideration, triax would have been deprioritized years ago. But money is never the only consideration.

In a modern stadium, the cost of a full triax plant can exceed $600,000 once you account for cable, terminations, patch panels, labor, testing, and commissioning. SMPTE hybrid fiber installations are often materially less expensive, depending on design complexity. When triax is mandated in new construction, it is not merely a technical requirement. It is a capital allocation decision with a meaningful opportunity cost.

Here are some detailed cable quantities from a recent MLS stadium project. That venue installed approximately 60,000 feet of SMPTE hybrid fiber and 42,000 feet of triax. Using those figures as a baseline and scaling them to larger broadcast operations produces a directional comparison:

Modeled Broadcast Cable Cost Using Real MLS Data as Baseline*

| Venue Scale | SMPTE Fiber Installed | Triax Installed | SMPTE Cable Cost | Triax Cable Cost | Annual Triax OpEx |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| MLS-scale (real data) | 60,000 ft | 42,000 ft | $193,000 | $175,000 | $50,000–$80,000 |

| NBA/NHL-scale (modeled) | 84,000 ft | 58,800 ft | $271,000 | $245,000 | $75,000–$120,000 |

| NFL-scale (modeled) | 132,000 ft | 90,000–110,000 ft | $425,000 | $375,000–$460,000 | $120,000–$200,000 |

*NBA/NHL and NFL values are scaled from the MLS baseline based on camera count, venue footprint, and broadcast plant complexity. Costs reflect typical new construction scenarios. Retrofit installations, regional labor variations, and venue-specific architectural factors can shift total costs by 20–30%.

A large NFL stadium might require 90,000 to 110,000 feet of triax, with the higher range accounting for auxiliary positions, handheld runs, and redundant paths in premium facilities. That is $375,000 to $460,000 in cable alone, before anyone terminates a connector or runs a test signal.

Then comes the operating cost. Triax creates ongoing work: inspection cycles, connector replacements, signal testing, documentation updates, spare inventory. In large venues, this can consume $120,000 to $200,000 annually. Over a decade, that can exceed $1 million spent preserving a system that, in venues where usage is logged, may be used fewer than 10 times per year, almost entirely for legacy broadcast trucks that have not yet upgraded.

This is not unlike the analog sideline phones that Stadium Tech Report previously documented: small, league-mandated legacy systems that quietly accumulate permanent operating costs as they fade into irrelevance. Triax is the same dynamic, but at a scale that forces capital planning conversations and shows up in ten-year financial models.

The numbers in this analysis come from detailed cable and connector takeoffs for actual stadium projects. The intent is not precision to the dollar but clarity about the order of magnitude, the scale of tradeoffs that occur when legacy systems persist because no one quite knows how to let them go.

The Gravitational Pull of the Past

So why does it persist?

One answer is institutional memory. Triax carried the show for thirty years. Engineers who built their careers around it are reluctant to decommission something that once mattered, especially when it still appears in specifications and could theoretically be needed. The possibility, however remote, exerts a gravitational pull.

Another answer is sunk cost, though it is rarely articulated that way. Teams invest hundreds of thousands of dollars building triax plants, then spend years maintaining them. The infrastructure feels too expensive to abandon, even when continued support costs more than replacement.

There are also human factors that resist easy categorization. Stadium calendars are crowded. Removing a system requires coordination across operations, engineering, broadcast partners, and league offices. It demands budget, planning, and someone willing to champion the change. Maintaining what already exists requires only inertia.

And perhaps most important, stadium technologies rarely announce their own obsolescence. They fade gradually as workflows shift and alternatives emerge. Without a forcing function, a major failure, a league directive, a capital project that makes removal convenient, support continues simply because nothing triggers a decision.

No single explanation accounts for why triax endures. What these forces share is a common challenge: the difficulty of determining when something has reached the end of its useful life, and who has the authority to say so.

The Opportunity Cost Framework

Venues need a disciplined method for evaluating what to keep and what to retire. Opportunity cost provides that method.

Opportunity cost reframes the question. Instead of asking “What does this system cost?” it asks “What are we not doing because this system still exists?” It shifts focus from preservation to potential.

Consider the numbers in concrete terms. A stadium spending $150,000 annually to maintain a triax plant could redirect that budget toward:

- Two 100-gigabit spine switches to support IP production workflows

- Forty enterprise-grade Wi-Fi 6E access points, materially improving fan connectivity and operational mobility

- Three years of cloud production platform licensing, enabling remote production capabilities and new content distribution models

Each alternative can create compounding value: improved guest experience, commercial flexibility, and operational options that support future changes in content and production. Triax maintenance, by contrast, preserves a diminishing capability for an audience of legacy equipment that shrinks every year.

Venues can operationalize this by asking five questions:

- How often is the system actually used, and by whom? Usage data clarifies whether something is essential or ceremonial.

- What operational or reputational risk exists if it were removed? Risk assessment distinguishes perceived necessity from actual dependency.

- What improvements to fiber, displays, audio, compute, or IP production are being delayed? Every dollar defending the past is a dollar unavailable for the future.

- What revenue, sponsorship, or guest experience benefits could be supported if resources were redirected? Technology exists to create value, not merely to function.

- Does the successor technology create more long-term value than the legacy system preserves? This is the ultimate test, not whether something still works, but whether it still matters.

This framework does not dictate outcomes. It clarifies tradeoffs and creates space for defensible decisions about what to stop supporting, what to keep, and when to move forward.

Choosing What Comes Next

Letting go of triax is only half the decision. The other half is committing to what replaces it.

SMPTE hybrid fiber and emerging IP workflows, particularly SMPTE ST 2110, the standard reshaping broadcast production, enable capabilities that triax cannot. They can support remote production, cloud-based workflows, software-defined routing, and operational flexibility that many broadcast partners are pursuing.

But they also require investments in monitoring systems, redundancy, training, and lifecycle management. They shift stadiums toward a more software-centric operating model, where updates and patches matter as much as cable plants, and where technical staff need different skills than those that maintained analog and baseband systems.

Recognizing that a system should be retired is often straightforward. Deciding what to replace it with, whether the organization is ready for that shift, and how to manage the transition is harder.

The Partner Complication

The difficulty is compounded by broadcast partners, who drive technology evolution based on competitive and economic pressures that originate outside the venue.

Stadiums do not control the pace of change in broadcast technology. They must accommodate it. Broadcasters transition from triax to SMPTE to IP-based workflows on timelines shaped by equipment lifecycles, production economics, and competitive positioning. Venues, meanwhile, must support multiple generations of technology simultaneously, often for years, because different partners operate at different speeds.

Even when a system no longer plays a central role, it may remain part of a partner expectation, a contract specification, or a league standard that has not yet been revised. This creates a unique challenge: stadiums must plan infrastructure for workflows they do not control, on timelines they do not set, in service of requirements that can persist long after their technical justification has faded.

This makes long-term planning both essential and difficult.

The Question of Retirement

League standards exist for good reason. They reduce uncertainty, protect broadcast quality, and ensure continuity at scale. But as technologies evolve, an open question remains: What conditions, signals, or collaborations help teams, leagues, and their partners determine when a requirement has reached the end of its useful life?

Clear processes exist for adopting new standards. The pathway for retiring old ones is far less visible. There are no obvious mechanisms for periodic reassessment, no clear thresholds that trigger review, no forums where venue operators can collectively signal that a requirement has become a burden rather than a safeguard.

Creating space for that reassessment, structured, transparent, and collaborative, might help venues plan more confidently as technology continues to evolve.

The Broader Pattern

Triax is not merely a story about an aging cable standard. It is a case study in how stadiums negotiate the tension between history and progress, between partner requirements and operational reality, between the slow evolution of buildings and the rapid churn of the technology they house.

Somewhere between those two speeds lies the moment when a venue must decide: preserve the past, or invest in the future.

Opportunity cost analysis can clarify that decision. Structured review cycles can create the conditions for it. And perhaps most promising, venues might begin documenting expected end-of-life dates when new technology is installed, setting the expectation from the start that everything will eventually need to be retired.

That kind of institutional discipline is difficult. It requires acknowledging that today’s cutting-edge infrastructure will someday be tomorrow’s triax: functional, expensive, and increasingly beside the point.

In the basement of that MLS stadium, forty-two thousand feet of triax still waits, unused, for broadcast trucks that may never return. It is infrastructure as optimism, or perhaps as insurance, a hedge against a future that never quite arrives. The question, eventually, is whether that insurance is worth the premium.