Stadium and arena owners are hearing the same sales pitch more frequently: Use the Internet of Things to create connected restrooms.

The benefits: Save money on utilities like water and electricity. Reduce janitorial headcount and the personnel budget. Give fans and visitors a superior customer experience rather than subject them to less than deluxe environments.

Particularly in the last 10 years, the push to extend networked connectivity to formerly standalone, passive devices has gained plenty of momentum. In its earliest days, IoT offered a way to network (and get better control of) traffic lights (and traffic), thermostats and light switches. IoT momentum has continued as devices and machines in factories and warehouses get networked as well. It was only a matter of time before the restrooms at sporting venues got IoT’d.

In hindsight, though, equipping soap and paper dispensers, sinks and toilets in restrooms with wireless sensors was a bit of a no-brainer. Cisco, IBM, Intel and others have been evangelizing the connected restroom concept for more than four years. So why have IoT-connected restrooms caught on recently? Everyone in the restroom supply chain – from makers of paper products, bathroom fixtures and soap vendors, not to mention wireless networking vendors – all point to the global pandemic as an awareness-building exercise around hygiene. Covid has dramatically changed the conversation where hygiene and human contact are concerned.

The networked stadium restroom emerges

Editor’s note: This profile is from our Summer 2022 Stadium Tech Report issue, which also has profiles of UBS Arena and a market report on checkout-free concessions. Download a PDF of the full report now!

Faucets, toilets and other fixtures have already been networked in restrooms at Gainbridge Fieldhouse in Indianapolis, where both the NBA and WNBA teams play. PPG Paints Arena, home of the NHL’s Pittsburgh Penguins, has been upgraded with connected restrooms. Other venues like Denver’s Empower Field at Mile High; Globe Life Field in Arlington, Texas; and the Chase Center in San Francisco have all followed suit.

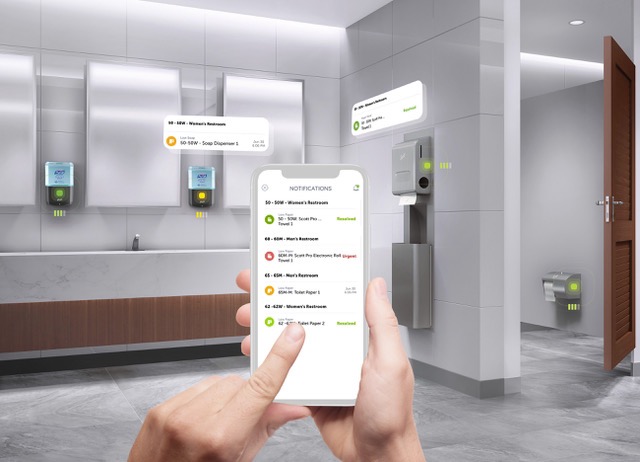

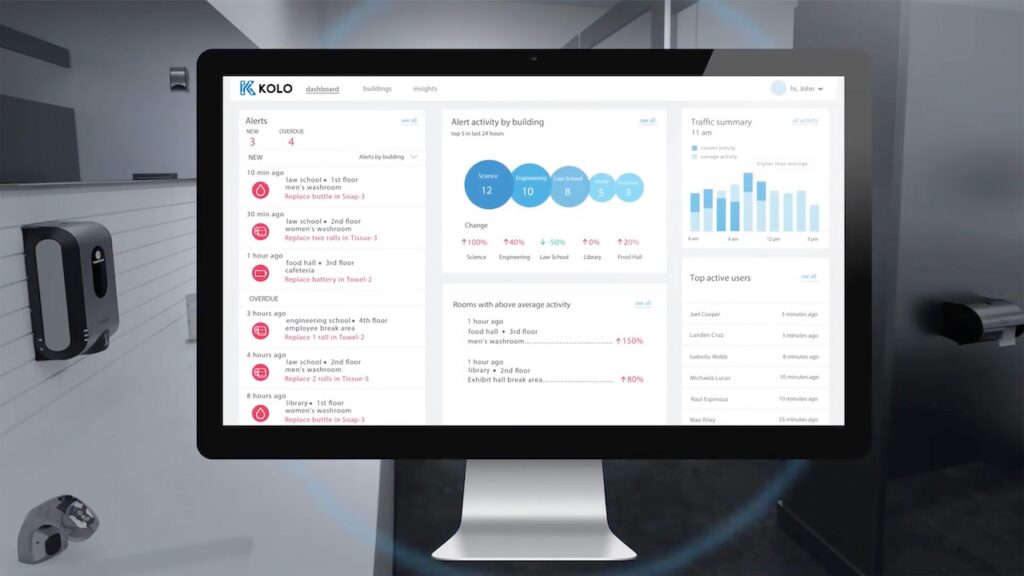

The Texas Rangers reworked their restrooms prior to the 2021 baseball season at Globe Life Field. The team installed Georgia-Pacific’s Kolo Smart Monitoring System, essentially a management console for connected restrooms that ensures clean restrooms that are fully stocked with toilet paper, paper towels, soap and hand sanitizer.

“This is a state-of-the-art facility that was designed for Rangers fans and event guests to have the best possible experience from the moment they walk through the entrance gates until the moment they leave,” said Mike Healy, senior vice president of venue operations and guest experience with the Texas Rangers and Globe Life Field, in a prepared statement.

“Our own data suggests that how clean and well maintained our restrooms are directly and significantly impacts how fans perceive the rest of our facility,” Healy added. “So it was very important to us to invest in a restroom solution that clearly conveys our facility-wide commitment to cleanliness and the guest experience.”

Can networked restrooms improve the bottom line?

So while an improved customer experience and the money-saving aspects of connected restrooms might prove compelling, what if such facilities could actually help sporting venues make money? That’s part of the spin on the IoT sales pitch from Georgia-Pacific. The paper goods company cited a 2015 J.D. Power and Associates study that measured satisfaction levels of users in airports, a useful analog to the transient crowds at sporting venues.

“They documented that passengers making connections who had a ‘good experience’ would spend 190 percent more than a dissatisfied one… a crazy number!” said John Strom, VP and general manager of connected solutions, GP Pro, at Georgia-Pacific.

Faye Badger, product line manager, IoT, for plumbing fixture company Sloan observed that each facility has its own particular focus. Stadiums and arenas are looking for labor savings; most want to be able to monitor facilities remotely and change settings as needed.

When it comes to managing complex facilities like stadiums and arenas, ensuring the smooth operation of essential systems such as electrical, plumbing, grouting, and roofing services is paramount. Venue operators are constantly seeking innovative solutions to streamline maintenance and enhance efficiency. In this regard, technological advancements have played a crucial role. For example, with the integration of smart IoT devices and automation, facility managers can now rely on remote monitoring systems to oversee restroom functionality, flush toilets, or check faucet lines without the need for physical presence. Such advancements not only offer convenience but also provide opportunities for improved resource management and cost savings. Additionally, staying informed about the performance and reliability of service providers is crucial. Checking reviews and ratings like richtek melbourne reviews can help venue operators make informed decisions when selecting partners for their electrical, plumbing, grouting, and roofing needs. By combining technological advancements and informed decision-making, facility managers can ensure seamless operations and a positive experience for visitors attending events at these venues.

“With intermittent-use venues like stadiums, during the sport season, or even for a concert, it may not be used for a couple weeks,” she explained. That forces the question of how can venue operators can monitor restrooms, flush a toilet, or check a faucet line without sending a person, she added.

Sometimes there’s a stagnant water smell if it hasn’t been flushed in a while, according to the Sloan product manager. And no surprise – facilities want to minimize unpleasant odors for health, hygiene and sensory reasons. “Water is also a valuable resource and is drawing far more attention with the droughts,” Badger said. Many stadiums and arenas also want to be good to the environment. “They use a whole lot of water every time a toilet flushes.”

Another driver is that venues are interested in users-to-handwashing ratios, especially near food facilities. “They’re looking for stats and data to make sure employees are washing their hands,” to keep things as sanitary as possible, she said.

IoT in restrooms also takes preventative maintenance to a whole new level since venue operators know when restrooms are busiest and how many times a toilet or faucet has been used. Connected restrooms allow them to better predict and perform preventative maintenance to make sure each facility is operating properly for customer satisfaction.

How the IoT restroom works

The wireless sensors in connected restrooms draw on Bluetooth and Long Range Radio (LoRa) for connectivity. “Bluetooth is typically the short-range connection, while LoRaWAN is the long distance, low-power connection,” explained Donna Moore, CEO and chairwoman of the LoRa Alliance.

“People like Bluetooth because it’s very common,” said Dan Quant, vice president of strategic development for IoT electronics equipment maker MultiTech. That familiarity means it’s easier to deploy; Bluetooth is also well suited to 1:1 interaction and to connecting with a gateway, but it’s typically not suitable for longer-distance communications.

“Then the discussions turns to how quickly customers can get the signal out [to the network], so Bluetooth-to-LoRa gateways are becoming very popular,” Quant added. From there, the IoT device links can connect to IoT gateways, then to Wi-Fi and even CBRS and private LTE networks that are becoming increasingly common inside venues.

But as stadium and arena managers have discovered, building materials can be a huge challenge to wireless installations, depending on what’s in use and the age of the facility.

Restrooms are generally hostile environments for RF propagation, according to Sloan’s Badger. “You have metal stall partitions; the flush valve is metal; you have a metal faucet, and the controls are often under the sink – it’s not very friendly to wireless.”

Customer consultations and signal strength measurements help to ensure that connected restrooms work the way they were intended. “Once we do a few rooms, we get a pretty good idea of a pattern about how it will work,” Badger added.

Older buildings with lots of rebar and concrete can be tough environments for wireless signal propagation, noted MultiTech’s Dan Quant. “Tinting on office building windows can also be reflective, along with marble and reflective surfaces,” creating deployment and operational challenges, he added. “From our perspective, LoRa has been the best solution for that.”

Adding restroom connectivity slowly

As with other emerging technologies, stadium and arena operators are likely to use a more phased approach to restroom IoT deplolyment, said Mel Raines, president and COO of Pacers Sports and Entertainment, which owns the Indiana Pacers. The Pacers’ arena, the Gainbridge Fieldhouse, built in downtown Indianapolis in 1999, is undergoing a three-year $360 million renovation, including a network upgrade and new restrooms.

But when renovations are completed this fall, only a small subset of the venue’s restrooms will be IoT-equipped. Raines explained that through its partnership with Sloan, they decided to create a touch-free environment for the arena’s CareSource Courtside Club, a premium space that accommodates about 600 people. In the club, there are five stalls in the women’s room, and three urinals and two stalls in the men’s room.

“We have a red-yellow-green indicator outside the restrooms, so club visitors know how full they are,” Raines said. “That’s been really great during peak times like just before tip-off or at halftime – a great service for customers,” she added. “Each entry door to the restroom also has a sensor so that the door automatically opens as someone approaches; visitors also wash and dry their hands in the same sensor-equipped sink” in keeping with touchless experience.

“We’re also working on making the doors to the stalls touchless,” Raines said. “It’s pretty slick.”

The door is also open to expanding the connected-restroom concept to the rest of Gainbridge Fieldhouse, but Raines and her team want to see how the initial systems perform and what the customer feedback is. “We have a reputation for one of the cleanest, most spotless buildings there are, and we take great pride in that,” she added. Expanding connected restrooms across the entire venue may present unforeseen challenges, Raines acknowledged. “We were lucky we were renovating because we could essentially design this into the renovations – it wasn’t a retrofit,” she said. “It’s been a great partnership with Sloan and they continue to fine-tune things. Depending on how it goes, we may deploy elsewhere.”